A Tale of Two Mothers: Love Beyond Life and Death

Celebrating the extraordinary women who shaped one life with unwavering love and sacrifice.

ORIGINALLY POSTED ON APRIL 1ST, 2018

On this Mother's Day, I am reposting a story I originally shared on April 1st, 2018, a day that marked the extraordinary confluence of Easter Sunday and April Fools' Day.

Today, I find myself reflecting on the two mothers who shaped my life in the most profound ways. One gave me life, the other raised me, and both loved me deeply. And though our time together was cut short by the cruelest of circumstances, their love has never left me. Today, I want to say the words I never had the chance to tell them in person - thank you, I love you, I am who I am because of you.

This is the story of my journey to find my birth mother, to understand my origins, and to come to terms with the incredible love and loss that have defined me. It is my personal story of deep yearning, relentless searching, and the ultimate gift of closure. And it is a love letter to the two women who made me who I am, even as one remained forever beyond my reach.

This is for all the mothers out there.

April Fools & Easter Sunday and the Confluence of Two Remarkable Stories

Born on an Easter morning and adopted into a loving family, I grew up haunted by the mystery of my origins. With each passing year, the longing to know my birth mother grew stronger, propelling me on a relentless search for answers. Little did I know that the universe had a twist in store, intertwining my tale with the most unlikely of dates - April Fools' Day.

THE TURNING POINT

On April 10th, 1977, my birthday would land again on Easter Sunday, and I would turn 11 years old. At the same time, a great aunt of my adopted family came for a visit from England, bringing their family tree that dated back almost a thousand years.

I was simply mesmerized by this. I completely soaked it up and was delighted to see our family’s history. But that’s when it hit me like a brick: This was not my blood, this was not my family's story.

So I asked my adoptive mother when would I be able to see my family tree and my mother looked at me and quipped, “You can't know that. You can’t see your family tree. That's illegal.” Illegal?? I almost fell over. Though I was only 11, I could still immediately recognize this injustice. How could it be illegal for me ever to know my family story?

As fate would have it, the very next day, I would come across an article in the now-defunct newspaper, the Sacramento Union, showcasing adoptees in search of their birth families. I quietly took the newspaper article and wrote down the addresses of the adoption research organizations that had been listed. I quickly sent several letters to these organizations using my best friend Karen's home address as the return address. I didn’t dare let my adoptive mother know what I was up to because I knew she would be devastated.

I gave these organizations the little information I had of my birth mother, like her age, hair/skin color, and religion, and asked them if they would help me find her. One week later, I would get responses from all these different organizations and they all said the same thing; From the information you've given us you’re very young, your mother is young, and until you turn 18, legally, there is nothing we can do for you -- but don’t worry, you have plenty of time.

Well, unbeknownst to me and these adoption organizations, my birth mother was battling breast cancer and would die a year later, in 1979, at the age of 35. I would not know this until nearly 20 years later.

After receiving the responses from these adoption organizations, I would confess to my adoptive brother about my search and show him the handful of letters I had received. He would immediately tattle this to our mother, causing an irreparable explosion in our relationship, a chasm we would never recover from.

My adoptive mother was hurt, rejected, and could not understand why I had done this: I had been adopted into such a good family. How could I betray them like this?

I tried to explain to my adoptive mother over and over I was not rejecting them. I wanted to know where I came from. I simply wanted to know my family story. I wanted to see where I was on my own family tree. She couldn’t hear this. Unexpectedly, my adoptive mother would blurt out in a moment of rage, “Just so you know, your name is Marcella Anderson!”

I reeled backward. I had a different name? I was given an actual name at birth? It never dawned on me that my birth mother had given me a name that would ultimately be changed upon adoption.

I held on to this name, Marcella Anderson, close to my chest, knowing this would be the breadcrumb I would pursue later. Some day.

But even the thought of this pursuit would be interrupted in 1985 when my adopted mother, 54 years old, was diagnosed with colon cancer, stage 4.

In the blink of an eye and at the age of 18 years old, I would become my adoptive mother’s sole caregiver, giving her 8 to 12 injections a day, cleaning out her colostomy bag, bandaging a foot-long incision that was split wide open with infection. I would endure my adoptive father, for the first time, beating me, throwing me down a flight of stairs, kicking me in the stomach, blaming me for my mother’s cancer, freaking out over her pending death. He couldn’t handle it and took it all out on me. It was a horrific turn of events.

In an instant, my life was consumed by a nightmare. Five and a half months into this bad dream, my mother’s bowels became blocked, and she began running a fever. I called her doctor, who instructed me to call an ambulance and take her to Auburn Faith Hospital for testing.

My mother was overweight, and my father and I could not carry her down a narrow set of stairs, so once the paramedics arrived, they hoisted her onto a gurney and immediately laid her flat. My mother went into a state of panic; she obviously had a tumor that had metastasized somewhere in her airway, and if laid flat, she could not breathe whatsoever.

I explained this to the paramedics, and they immediately popped her upright, and we continued in the ambulance to Auburn Faith Hospital. Once we arrived, they immediately whisked her away from me and my supervision so she could undergo a sonogram in the hopes of locating the obstruction in her bowels.

I knew we were getting close. The doctor said my mother most likely had about a week to live. I spent the last 5 ½ months caring for this stoic registered nurse. During this time, we never spoke of her pending death. My mother pretended to me that she was not going to die. I took her cue and did the same, though we both knew death was undoubtedly on its way.

We were a family that never expressed our emotions. We rarely ever verbally expressed our love for one another, and now, so close to death, neither my mother nor I could bear a heartfelt and vulnerable conversation. So, instead, I practiced to myself what I was going to say to my adoptive mother when the time was “just right.” Over and over, I rehearsed what I wanted to say, expressing everything I had been bottling up. I was planning on closing that painful gap in our relationship caused by my search for my birth mother. I would ultimately set the record straight, letting my adoptive mother know how much I loved her and that, yes, indeed, she was my “mother” and irreplaceable.

Despite all this practice and preparation, I didn't know that opportunity would never come. A moment after my mother was wheeled away from me to undergo the sonogram, the doctor would return within minutes, pale-faced. He walked up to me and my father, both standing in the hallway, and announced, “I'm so sorry, she just died.”

What?!

Just like that? What do you mean? But I didn’t get a chance to tell her everything I wanted to say! I’ve been practicing. Waiting for the right moment. This can’t be….

What happened next I will never be able to shake. I went rushing into the testing room, and there I could see my mother on the gurney, lifeless, and I knew why.

They had laid her flat. Within a minute of leaving my care, my warning would be neglected, and my mother would be laid flat, where she would ultimately suffocate to death.

As quickly as she died, so did any opportunity for me to tell her how much I loved her and everything else I had been rehearsing in preparation for that “perfect moment.”

Heaving and bawling over my dead mother’s body, I would look up over my head, remembering stories about how after a person dies, their soul would hover over their body. I wanted her to see my face. To hear the words that I had been holding back all this time. Instead, I would gasp when I looked up, seeing the last thing my mother saw before she died: a poster plastered to the ceiling that read, “You only live once, but if you live it right, once is enough.”

What words to die to, I thought, and I sobbed even harder.

I would be wracked with guilt for several years and felt searching for my birth mother would be a betrayal of my love for my adoptive mother.

It took time and much convincing that this was not a betrayal until finally I would somewhat recover and, once again, pick up my search for my birth mother where I left it when I was eleven.

I would now begin looking for the Andersons.

I had no clue where they were. I was so desperate that many times, as a teenager, I would imagine that my family members were the owners of Pea Soup Andersens Restaurant and Inn. Pea Soup Andersen’s had an iconic windmill and was a traveler’s destination along Interstate 5 in central California. Our family would pass by it during family vacations. I often imagined entering this restaurant, recognizing the owners’ facial features as my own, ultimately reuniting once again with my birth family, and living happily ever after.

My search for the Andersons, however, proved fruitless. I hired researcher after researcher, and none of them could find my Andersons—not even a trace.

For another eight years following my adoptive mother’s death, I would continue looking, turning up little clues, until I turned 30. It was with this birthday I made a promise to myself that this would be the year I would finally find my birth mother -- come hell or high water.

The one thing I had not been able to do was open up my adoption records. After enduring my adoptive mother’s reaction to my search, I didn’t have it in me to ask my adoptive father to sign for the release of my adoption records. I could not do this without his signature, and I could not bear the thought of causing him any grief or sense of betrayal as I had my adoptive mother. It was the opening of this file that seemed to be the only thing standing between me and my birth family, however.

At the time, I was living in Los Angeles, studying filmmaking, and one of my dearest friends, a notary public, had been watching me turn up nothing after nearly 20 years of searching. So, committing the ultimate sin, and, yes, crime, she allowed me to sign the papers as my adoptive father, requesting the opening of my adoption file, and she notarized his forged signature.

As you can imagine, she knew this was a crime, something she would never do under any other circumstance. However, she also knew my personal circumstances and took a bold and extraordinary chance. She knew the serious crime she was committing and told me if this ever came back to haunt her, she would deny it and say that her notary stamp had been stolen. I will always be eternally grateful to her for putting herself on the line like this. I knew it was a huge deal, and now, to this day, if she had not done this, I would still not know who the hell I am.

So, to spare my adoptive father the same suffering my adoptive mother endured, we forged his signature, sent off the notarized documents to the state, and two weeks later, my adoption files were opened and sent to me. This was when I discovered that my adoptive mother had put me on a 20-year-long wild goose chase.

My last name was not Anderson. It was Funston.

For 20 years, I had been looking for the wrong people.

My adoptive mother had to have known my last name was Funston. I was born in San Francisco, where there is a Funston Avenue and a Fort Funston named after the legendary General Frederick Funston, my natural great-grandfather. My adoptive mother had lived in San Francisco for a period of her life, so I find it difficult that she mixed up the name Anderson with Funston. I do not doubt that at the time my adoptive mother told me this false name, she knew it would mislead me because Funston would have been too easy to track down, particularly in San Francisco. Unfortunately, death would take my adoptive mother so quickly and unexpectedly she too would never be able to tell me what she always wanted to say: I was not an Anderson. I was a Funston.

Soon after I opened my adoption files, I hired the most remarkable researcher, Ida Knapp. She was simply brilliant. We would ultimately have to trick “the system” into giving us the rest of the story.

Ida began searching for my birth mother, whose name we found out from the open adoption records was Jane Funston.

We searched records across the entire state of California and finally the whole nation, far and wide. We could not find any trace of Jane Funston from death certificates to divorce records. My birth mother seemed to have vanished entirely from the face of the earth. It seemed fate had decided to keep me in the dark for eternity. But fate was not going to deter Ida Knapp. She told me what I needed to do next.

“Reinette, I want you to write to the San Francisco University Hospital where you were born, but I want you to write as your birth mother, Jane Funston, saying that you have a daughter who is having pregnancy complications. Request your, or Jane’s, medical records, and let’s see what we get.”

So, I did just that.

A week later, I got the medical records of my birth mother, Jane Funston, and that’s when I found out she returned to the same hospital 4 ½ years later and gave birth to my natural half-brother, Damien McLean.

I thought, “I have a half-brother from my mother, of the same blood?” This meant the world to me.

We were never able to track down Jane. But in a matter of a day or two, we tracked down Demian through his father, Jane’s former husband, Michael McLean, living in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where Jane ultimately had died.

I got on the phone, not knowing what to expect, and called Michael McLean. He answered in a low, soothing voice, and as soon as I told him I was the daughter of Jane Funston, he said to me,

“We have been waiting for your phone call for 30 years. “

I was flabbergasted. He continued, “We knew that if there was anybody you would track down to get to your mother, it would be us. We were the most settled and “trackable.” We also knew that if you had not been put up for adoption, once your mother had died, you would've come to live with us like your brother, Demian, had. So we always thought of you as the child we never had.”

I explained to Michael how this 20-year-long search continuously turned up nothing and that, ultimately, we could only find Jane through Demian. Michael explained that I could not find my mother because when she died, her name was no longer Jane Funston. It was Istarra Yedlowski. Istarra Yedlowski?

Istarra what?

Being the good hippie she was, she changed her first name from Jane to Istarra and then married a man with the last name Yedlowski.

Istarra Yedlowski. That would be the name she would die with. Well, no wonder I couldn’t find her.

Michael would continue, “Why don't you call Pat, my wife? She would love to hear from you.” So I did, and when she answered the phone, I told her who I was. She excitedly exclaimed, “The Baby! The Baby is calling! The Baby is calling!” We were both in tears.

THE REST OF THE STORY

The dust has been settling over the years, and the mystery that shrouded my birth family has dissipated for the most part.

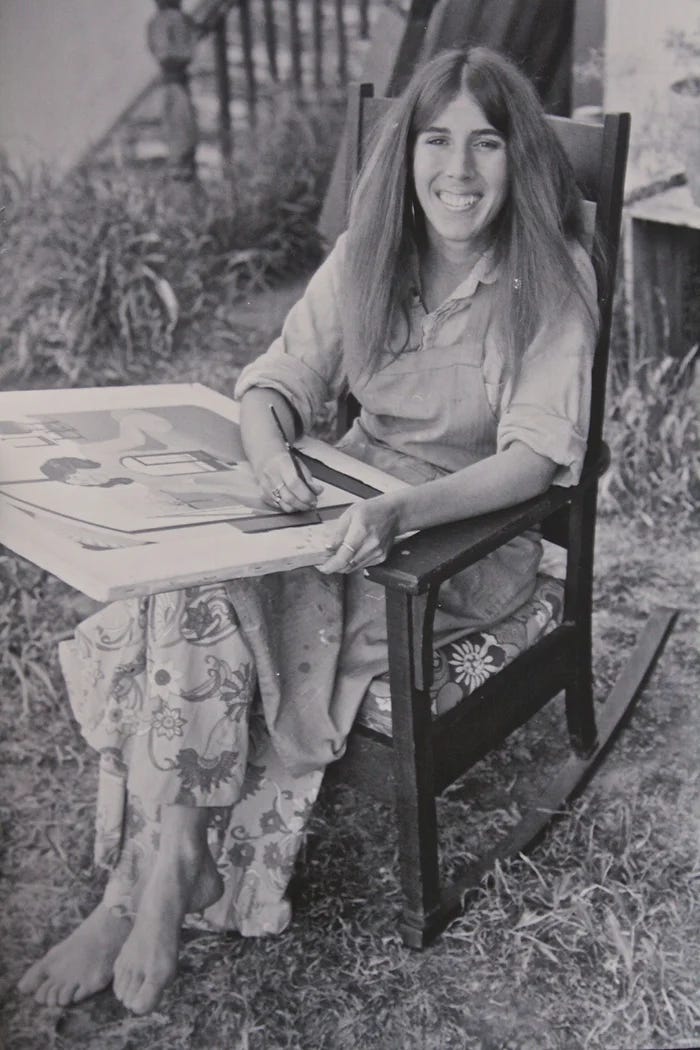

I had found my natural family and have them in my life, including Jane’s friends, her paintings, and even the front door to her artist study, which has her hand prints on the backside, pressed in white paint. When I press my hands into the door, I can tell that our hands are one and the same. My handprint fits Jane’s like a glove.

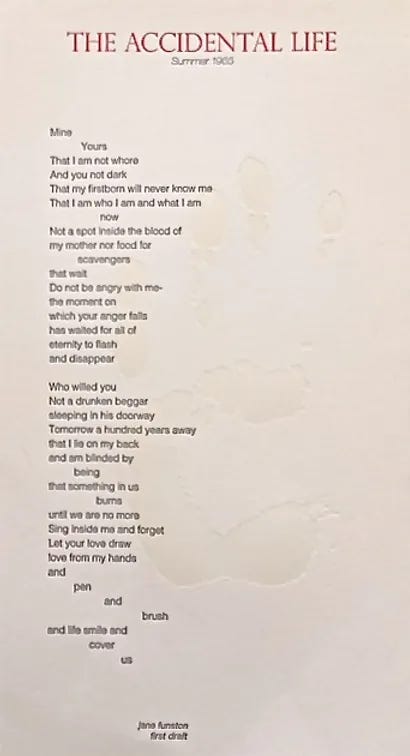

Most importantly, Jane left behind a poem about “her firstborn she would never know” called The Accidental Life. I have it memorized and say it to myself every single day to this day. But for years, I was under the impression that Jane had died sometime in February until just a few years ago when I was researching on the Internet and came across her death certificate.

I was told that Jane, like my great-grandfather, Gen. Frederick Funston, had a wicked sense of humor and loved to pull pranks on her friends and loved ones. This seems just as true in death as it was in life because when I looked at Jane’s death certificate, I discovered she did not die in February as I had thought, but on April 1st, April Fools Day, of all the days. I can’t help but feel that not only in life, but also in death Jane pulled a fast one on me.

Today, Easter Sunday and April Fools Day fall on the same day, a day marked by the confluence of the most remarkable stories—stories of deep yearning, intrepid searching, and, ultimately, much-needed closure.

So it is today that I say the words I was never able to say to my two beloved mothers: I love you. I thank you both for the life you have given me and for making me who I am today. Life is good, and I look forward to meeting (again) on the other side so that I can tell you both in person.

If you find these interviews and articles informative, please become a paid subscriber for under 17¢ a day. I don’t believe in paywalls, but this is how I make a living, so any support is appreciated. Either way…. it’s available to you….

On, Reinette! What a beautiful, heart-wrenching story. You are truly remarkable. I lost it when you got to the part where you found your brother and how they had been waiting for you all of those years. I am so happy for you that you were finally able to fill in the missing pieces around your mother.

Adoption is never easy. I am the adoptive mother of two adult children, both adopted as babies. When we adopted our second child, they (Catholic Social Services) had just begun open adoptions. We were in a group with eight other couples and my then husband and I were the only ones who agreed to meet the birth parents. I think a lot of adoptive parents want to believe that they're the only parents. In the end, my daughter's birth parents chickened out. But, I wrote letters and sent photos for a while. My children always knew that they had been adopted (I'm horrified that this is kept from so many children) and when they got older I made sure they knew that I fully supported them if they wanted to look for their birth parents.

Much love to you, Reinette. XO

Deeply moving., beautiful story.